The European Commission has placed the EU’s delay in developing and adopting AI at the heart of the continent’s competitiveness problem. It has launched several initiatives to address this, including the buildout of AI infrastructure backed by a substantial amount of public funding.

Specifically, EUR 10 billion (split between the EU and hosting Member States) has been invested into AI factories, large data centres optimised for AI training. EUR 20 billion in public-private funding (a third being public) has been committed to building AI gigafactories, even larger clusters of AI-optimised computers. This infrastructure is supposed to boost cutting-edge AI development and finally bring Europe to the forefront of the global AI race.

There’s no doubt that Europe needs more compute. But it’s no magic pill to its competitiveness problem and the strategy raises many uncomfortable questions. Are the (giga)factories designed to support the current AI ecosystem? Will they help Europe catch up? Can they keep the continent’s technological sovereignty agenda on track? What research priorities will they advance?

Here’s what we at CEPS found in the eye of the storm.

A doppelganger network of hubs

The AI factories are supposed to become dynamic ecosystems where compute, data and talent converge. Yet where they’re located shows that a wide geographic distribution and their proximity to established, energy-efficient infrastructure – especially existing EuroHPC sites – are being prioritised over existing AI ‘hubs of excellence’.

This does make sense. AI training can be done remotely, so placing compute infrastructure next to talent isn’t necessary. Thus, a site chosen to instead optimise for available land, cheap energy and pre-existing high-performance computing in each country is indeed the best for that country.

But the Commission’s narrative about creating vibrant ecosystems that attract talent is essentially misguided. Talent won’t go to the factories – the factories must go to the talent. That’s why the network of AI supercomputers should be federated and allow for seamless remote access, so that it fully supports European researchers and innovators.

Where will the energy come from?

Electricity and water costs have become a major bottleneck for building data centres, which impacts where the gigafactories should be located more than the factories. A wide coverage of countries may be sustainable for the factories, conditional upon the sites optimising for energy efficiency within each country’s borders. Yet it may fall short of meeting the energy demands of the 100 000-chip supercomputers. The EU should concentrate the gigafactories in the countries that offer the cleanest power for the cheapest price if it wants to reconcile competitiveness with sustainability.

The energy question also challenges the provisionally planned use of the gigafactories for inference – the process of running a trained AI model. Placing the gigafactories in remote areas should be reconsidered because, contrary to AI training, inference demands low latency and proximity to end-users, and doesn’t require centralised workloads. Their scale and siting may make them sub-optimal for inference.

Avoiding the Nvidia dependency trap

Perhaps the most striking feature of the gigafactory plan is the almost exclusive reliance on Nvidia for chips. This wouldn’t be fatal for the factories’ sovereignty but only if factory users have full control of the software orchestration.

Unfortunately, operational control may not be guaranteed if the AI models are developed using the CUDA software layer, Nvidia’s proprietary set of tools allowing the use of GPUs for AI training. CUDA corresponds to an intermediary layer of the AI stack, sitting between the compute and model development, which could lead to inflexibility in the latter.

The solution isn’t just about diversifying GPU suppliers. The factories should prioritise open-source solutions linkable to other tools for the public good. Europe should also invest in alternative computing approaches that don’t depend on GPUs, along with strategic partnerships for supplying increasingly important components like memory chips. Otherwise, the initiative may replicate existing tech dependencies.

The wrong AI at the wrong scale

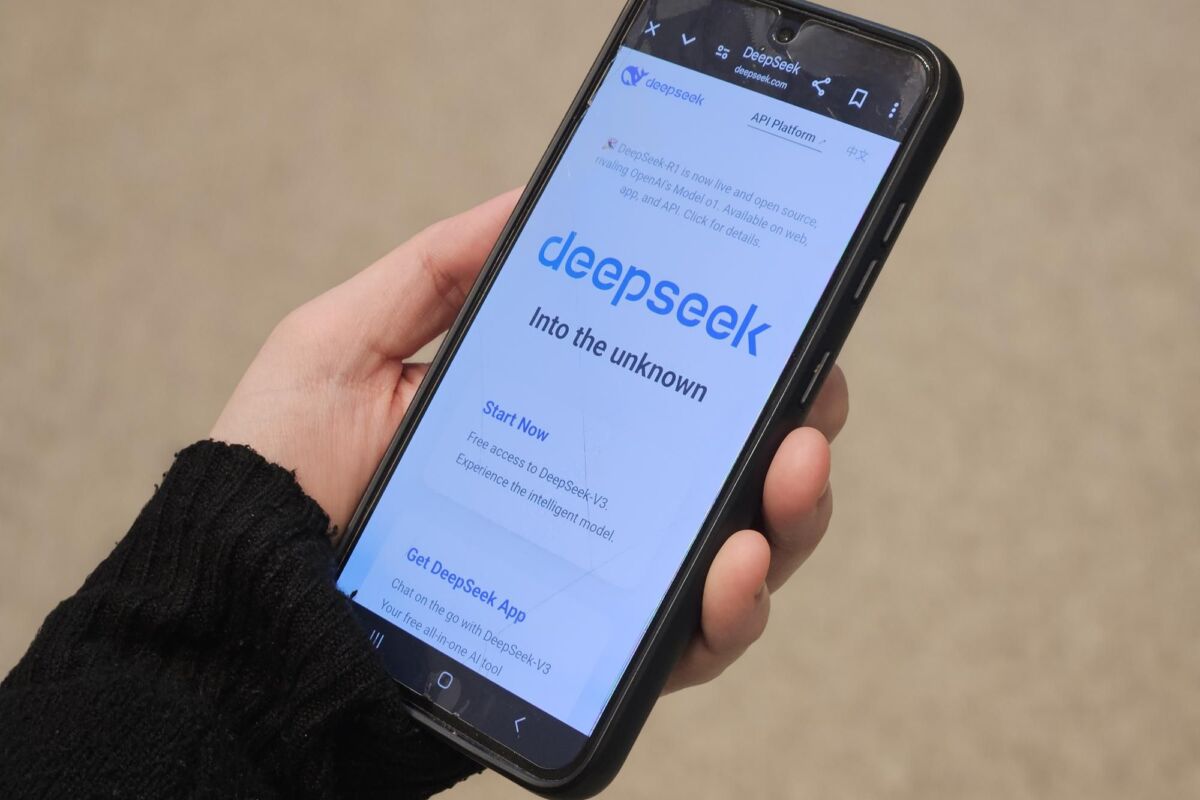

At its core, the AI (giga)factory plan is a leadership problem. Europe is emulating both big tech’s approach to AI and its ultimate goal for AI (to achieve artificial general intelligence) but with daunting private investment gaps and a very different social model.

Alas, the massive investments flowing into generative AI in the US and China will make it hard to ever ‘catch up’. But the technology’s continued unreliability and its increasing strain on electricity, present Europe with the opportunity to compete with alternative solutions which uphold its values. These may involve neuro-symbolic algorithms and neuromorphic chips, or simply smaller, specialised models.

Crucially, AI factories must include technical work on AI safety. With the future of AI research uncertain, what’s beyond doubt is that unreliable and unsustainable AI can’t be deployed at scale, whether in business, critical infrastructure or for public services.

Finetuning the gigafactories plan

For the gigafactories to boost Europe’s competitiveness and sovereignty, they need a much sharper strategy.

First, serve the compute to the talent, ensure the network of gigafactories can function as the cloud and mandate interoperability and collaboration. The infrastructure sites won’t substitute the existing research and innovation hubs.

Second, reconcile competitiveness with sustainability. Gigafactories must be concentrated in regions with abundant renewable energy and powered by additionally generated electricity at competitive prices. Energy consumption is the big, glaring elephant in the room.

Third, re-consider whether the gigafactories should support both training and inference. If their envisioned scale is non-negotiable, it implies location choices that may rule out inference or could require investment in fibre connectivity. Such trade-offs should be acknowledged early on.

Fourth, make infrastructure future-proof. Secure GPU supply from multiple vendors and invest in partnerships to ensure the availability of other increasingly important components. Prioritise open-source infrastructure solutions that can pool multi-vendor resources. All of this will be critical for reducing dependencies.

Finally, define strategic goals and long-term missions. What specific AI capabilities does Europe need? What alternative research directions can we promisingly pursue? How do we build trustworthy solutions? The recently launched Apply AI strategy and the newly announced Frontier AI initiative could steer gigafactories’ use towards the breakthroughs in safety and reliability that widescale AI adoption requires.

At a time when the EU is under pressure to become competitive and sovereign in AI, it should abandon any dreams for AGI leadership or digital grandeur. The best Europe can do is to bet on an alternative AI growth model, one that’s based mostly on proprietary technology and gradually morphs into a more autonomous stack.

What’s needed is a level of ambition that’s ‘just right’ – that doesn’t hyper-focus on scale but rather on reliability and is tailored to what industries, public services and researchers really need to innovate.

To read the longer report that this commentary is based on, please click here.