Europe is facing a defining moment in its approach to science, research and innovation. As geopolitical tensions mount and investment in dual-use technologies surges, the EU is being called to reimagine its research policy – not just for strategic autonomy but for lasting societal relevance and real global impact.

At a recent CEPS dialogue on ‘Reimagining EU Research and Innovation Policy,’ this author focused on five asymmetries that policymakers absolutely must address if Europe is to avoid a future of diminished influence, declining trust and squandered opportunity. And the best way to avoid such a future is to build a truly (open) Science Stack.

Data asymmetry – or ‘Winter is Coming’

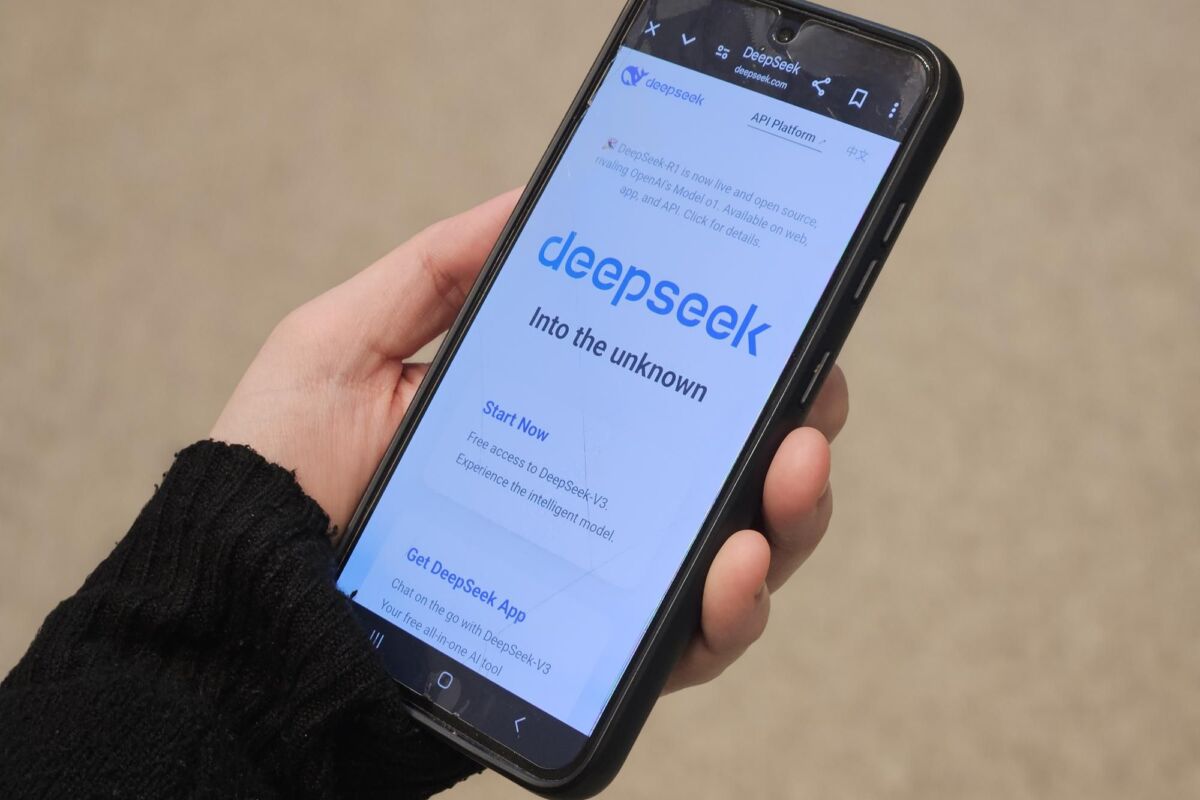

The foundation of modern research – especially in the AI age – is data. Yet access to high-quality, dynamic datasets remains highly concentrated among a few private actors.

Despite years of rhetorical support for data sharing, there’s been little progress made to foster systematic, sustainable and responsible data reuse. Without real incentives for data collaboration and investment in data stewardship, Europe risks entering a ‘data winter,’ where researchers and innovators are unable to access the very resources needed to compete or contribute meaningfully.

A Data Commons approach – governed by clear purpose, ethical principles and structured collaboration mechanisms – isn’t a luxury. It’s an existential necessity.

Information asymmetry – or lost in the labyrinth

Despite open science proclamations, information asymmetries persist – both when accessing research results and in terms of visibility into what research is being funded and conducted. The trend toward increased security-driven research, particularly in dual-use technologies and defence, threatens to make opacity worse. Billions of euros earmarked for ‘strategic autonomy’ may fund critical innovations – yet under conditions of restricted scrutiny and with minimal accountability.

That’s why transparency, including a publicly accessible map of research efforts across the EU, is essential – not only for scientific collaboration but also for democratic legitimacy.

Agency asymmetry – or who sets the research agenda?

EU Framework Programmes, like FP10, offer vital continuity but their technocratic language and insular processes often alienate those outside the Brussels Bubble or academia. The critical question remains – who decides what Europe should research… and why?

To correct this agency asymmetry, Europe needs to democratise its innovation agenda. A ‘100 Questions for Europe’ initiative could provide a public platform to crowdsource and deliberate the research priorities that truly matter – from climate resilience to mental health to digital rights. In this context, ‘digital sovereignty’ must evolve from a defensive posture to one that champions digital self-determination, enabling communities to shape not only data flows but research priorities themselves.

Such engagement could also provide much-needed social license for data re-use and research in an era of increased public scepticism and ethical concerns.

Computational asymmetry – federate, don’t centralise

AI and other computationally intensive domains aren’t just about raw processing power. Europe’s race to build more data centres and advanced infrastructure misses a crucial point – namely that computation must be mission-driven. Without federated models and cross-border collaboration, the continent risks reinforcing inequalities rather than unleashing innovation.

Europe’s strength should lie in its ability to collaborate across regions, disciplines, and borders – not in replicating a ‘build it and they will come’ model that has already failed to deliver efficiency or effectiveness elsewhere.

Skills symmetry – bilinguals, not just coders

Finally, while STEM education is vital, it’s insufficient on its own. Solving society’s most complex challenges requires ‘bilinguals’. These are individuals who combine deep domain expertise with digital fluency. Such hybrid thinkers – able to frame the right questions and assess the limits of technology – are essential for avoiding solutionism and promoting real impact. They also enable collective intelligence.

On top of this, we need investment not just in skills but in question literacy. What are we solving? Who defines the problem? What are the metrics for determining success?

In an era where strategic autonomy is reshaping policy frameworks, the temptation to build a ‘EuroStack’ focused on technological independence is understandable. But if that stack is built atop brittle foundations – rife with asymmetries in access, information, agency, computation and skills – it won’t serve Europe’s broader ambitions to advance research and innovation.

What we need instead is an (open) Science Stack – a holistic, polycentric architecture that blends data access, ethical guidelines, participatory governance and mission-driven infrastructure.

A stack that empowers – not isolates. A stack that listens as much as it leads.