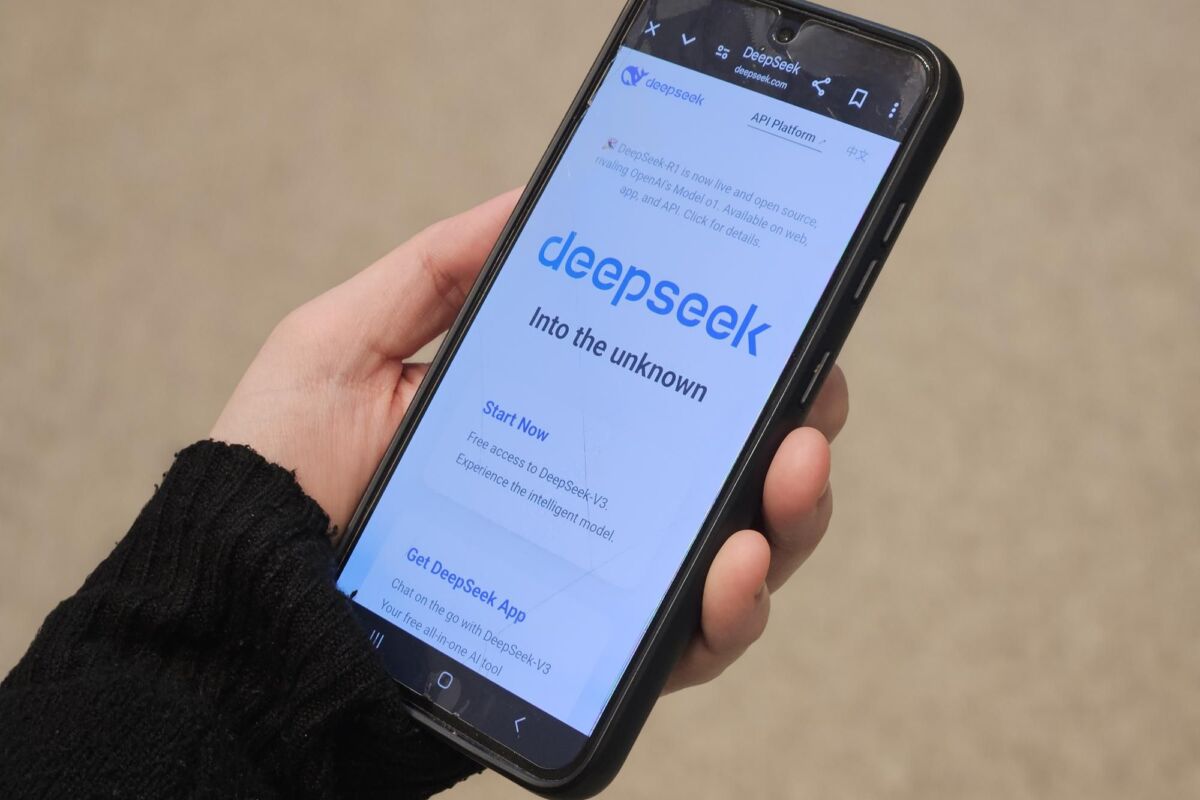

How to govern Artificial Intelligence (AI) has taken centre stage in the global policy debate, especially following the release of powerful generative AI systems such as Open AI’s ChatGPT, Google BARD and Meta’s LLaMA. Their spectacular ability to emulate human cognitive skills has triggered a real sense of urgency, if not anguish, among regulators and global leaders. Yet while there is broad agreement on the urgency, there is no alignment on what should be done, how to do it, who should do it, and – most importantly – why we should do it. And this is a big challenge.

Strangely enough, this sense of urgency was instigated by the same tech leaders that brought generative AI to the market. Emerging firms like OpenAI and DeepMind, with the support of ‘Big Tech’, started raving about an AI-generated risk of human extinction. They are flanked and inspired by movements such as the ‘effective altruists’, which cleverly juggle with the narrative of ‘utopia or annihilation’ to fuel the Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) industry or – as some call it – ‘God-like AI’.

In March this year, the same crowd asked for a moratorium on the training of large AI models. In May, they begged US senators to regulate them like the world did with nuclear weapons. Yet ten days later, one of them threatened to leave the EU if the AI Act eventually classifies generative AI as high risk. Since then, they have whispered into the ears of global leaders that action must be taken now, before it’s too late.

Leaders listened, perhaps too carefully. Ursula von der Leyen got so worried that she devoted a passage of her recent State of the Union address to the risk of extinction from AI. Joe Biden has spoken of an ‘enormous’ risk. Xi Jinping called for dedicated efforts to improve the security governance (and, naturally, state control) of AI. Rishi Sunak took the extinction narrative as grounds for a major international initiative on AI, embracing the rhetoric of utopia or annihilation to position his country as a global hub for AI governance talks.

Unpicking an alphabet soup of AI governance proposals

Over the past few weeks, governments, international organisations, and practitioners have offered a smorgasbord of new institutional architectures. Some (including Ursula von der Leyen) see the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) as a model for a future expert-led panel on AI. Others prefer to look to the civil aviation industry, and favour an ‘International AI Organisation’ (IAIO) that certifies jurisdictions, not companies. Some propose a Global AI Observatory (GAIO); others a global, neutral, non-profit International Agency for AI (IAAI). And yet another group of authors, featuring researchers from OpenAI and DeepMind, proposes as many as four new global agencies.

These proposals are unlikely to introduce enforceable guardrails on AI development. Those that look at the IPCC (or at a possible GAIO) can be implemented quickly – yet despite its high standing, the IPCC has not stopped us from wildly violating our planet’s natural boundaries.

More ambitious options would take longer to implement, due to the need to agree on the governance, powers, and composition of these institutions. They would also meet (understandable) resistance from organisations such as the International Telecommunications Union, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation, the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, the Council of Europe, the Global Partnership on AI, and several standard-setting organisations that have actively worked in this domain over the past few years.

Thus, why should we reinvent the wheel, proposing long-term solutions to a problem that arguable needs immediate action?

Because no matter how well-intentioned, this debate – currently as scrambled as that world-famous Tokyo crossing – has so far led to two worrying consequences. It has weakened ongoing regulatory attempts by national governments, and it has boosted global investment in Artificial General Intelligence (AGI), most likely at the expense of other, more compelling use cases.

A possible glimmer of light on the horizon

Consider the fate of the EU’s AI Act. Expected in early 2023, it was delayed as the European Parliament postponed its vote to include new provisions on generative AI. The final text was voted on by the Parliament in June, yet the trilogue negotiations that ensued are experiencing significant challenges.

As things stand, the Act will likely only be finalised in 2024 and will not enter into force before 2026. European Commission Vice-President Vera Jourová, who took some of the competences on digital policy after Margrethe Vestager’s departure, warned that basing the Act on ‘paranoia’ over generative AI is unlikely to do any good. Yet it may already be too late – the perceived need to take action is leading the Commission to look into softer forms of intervention, which mimic the (unenforceable) voluntary commitments already secured by the Biden administration earlier this year.

On the investment side, the risk is that an emphasis on the possible dangers from superhuman intelligence, and the ensuing competition to conquer this blossoming market, ends up triggering massive investment in AGI start-ups to the detriment of more compelling ‘AI for good uses’. These include the deployment of AI solutions to fight climate change, protect biodiversity, improve pandemic preparedness, nurture democracy, cure cancer, and save lives. For all these use cases, news is less encouraging. Just as venture capital investment in AGI increases, global private AI investment fell in 2022 for the very first time.

Among these worrying signs, a beacon of hope has come from the UN Secretary-General, who has announced the creation of a Multistakeholder Advisory Body that, rather than the risk of extinction, will focus on making AI available to all, including the ‘Global South’. It will also be made an engine of the Sustainable Development Goals.

We should all hope that this new Advisory Body leverages the work already done by the ITU, UNESCO, the OECD, and the Council of Europe, and steers the debate towards ensuring that AI enriches the lives of all humans (and helps save the planet to boot).

Indeed, before it really is too late to turn back.