Author: Apostolos Thomadakis

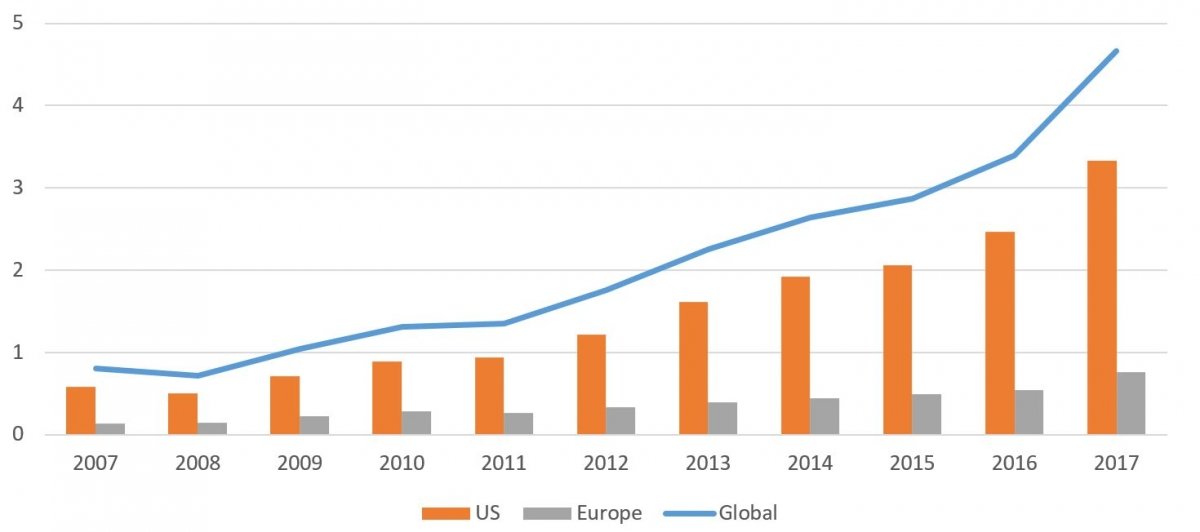

Growing demand in recent years for low-cost, easily tradeable, liquid and transparent investment products, resulted in the global expansion of the Exchange-Traded Fund (ETF) industry. Since 2007, global assets under management in ETFs skyrocketed from €0.8 trillion to €4.7 trillion – the market climbed 37% just in 2017. However, and despite the fact that US and European markets have each grown at a yearly average rate of approximately 18%, the latter represents only 16% of the global market.[1] The lag in the European ETF market demonstrates that: i) it is highly fragmented with multiple listings across many exchanges, ii) Europe’s capital markets have not been successful in attracting retail investors, iii) more on-exchange ETF trading is necessary, and iv) regulation and innovation can further develop and harmonise the market to move it towards more transparency and cost-efficiency.

Figure 1. ETFs’ assets under management (€ trillions)

Source: ETFGI.

Source: ETFGI.

What is an ETF?

An ETF is a fund that seeks to replicate the performance of a benchmark index, by buying the securities that make up that index or through synthetic replication using derivatives.[2] ETFs have been described as “genuine financial innovation” (Madhavan, 2016), as they combine the characteristics of both traditional open-end mutual funds (OEMFs) and those of closed-end funds (CEFs).[3] The special feature of an ETF is that its shares can be created or redeemed at the end of the day (like an OEMF), but at the same time can be bought and sold on the exchange intraday (like a CEF). In other words, it combines primary dealing with secondary trading; the former happens at the fund’s net asset value, while the latter at a mutually agreed spot price.

Table 1. Key characteristics of funds

Source: Author’s elaboration based on BlackRock (2017).

Source: Author’s elaboration based on BlackRock (2017).

However, only a small number of pre-approved institutional investors have the right to invest directly in the fund (i.e. end-of-day trades) – they known as participating dealers (PDs) or authorised participants (APs). This implies that PDs deal directly with ETFs while retail or other institutional investors access the ETF by trading on exchange or over-the-counter (OTC) through a secondary market. Therefore, PDs are acting as intermediaries between the ETF and secondary market investors, and thus are contributing to secondary market liquidity.[4]

How are ETFs regulated?

From a regulatory perspective, ETFs are traded on the main market and are therefore regulated under the Markets in Financial Instruments Directive. MiFID I, implemented in 2007, established a regulatory framework for the provision of investment services in financial instruments by credit institutions and investment firms and for the operation of regulated markets by market operators (though pre- and post-trade transparency requirements).[5] However, ETFs were not considered as MiFID instruments and thus there were no legal requirements to make trading volumes public. This is what MiFID II is trying to achieve by extending the transparency regime to all trading venues for shares and certain equity-like instruments, such as ETFs.[6] Since the beginning of this year, when MiFID II came into effect, all ETF trades have to be reported, meaning investors are able to gain a clear picture of the depth and breadth of ETF trading activity across all European trading venues.

Additionally, the majority of European ETFs comply with the provisions of the Undertaking for Collective Investment in Transferable Securities (UCITS) Directive.[7] The UCITS authorisation, which is recognised globally, is a guarantee of high and effective standards of disclosure and investor protection. The three most important provisions of a UCITS ETF are: i) diversification, so that no single holding is worth more than 20% of the fund’s NAV, ii) segregation, so that fund’s assets are separated from those of the ETF provider under the supervision of an independent custodian, and ii) liquidity, so that the ETF is liquid and open-ended and an investor can redeem his shares at any time.

The first major regulatory initiative specifically directed at ETFs, occurred in 2012. The European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) conducted a public consultation and established guidelines, which were then revised in 2014 and will be reviewed in 2018.[8] These specific pan-European rules for ETFs aim at further enhancing investor protection by requiring disclosure in the prospectus (as well as in the key investor information document (KIID) and any marketing communication) of: i) the policy regarding portfolio transparency and where information may be obtained and ii) specific risks related to secondary market investors (e.g. shares of the UCITS ETF are generally not redeemable from the UCITS ETF itself).[9]

What is the current situation?

In Europe, ETF turnover totalled €721 billion in December 2017, up by 63% over 2013. Despite the impressive performance, European turnover is equivalent to only 5.5% of US market turnover at end-2017 (€13.2 trillion). With regard to the number of ETFs, an all-time high of 6,607 European ETFs were admitted for listing on 23 exchanges, while the US had 2,085 ETFs on just three exchanges. However, just a mere handful of exchanges dominate trading activity. Together, Euronext Paris, LSE and Deutsche Börse generate more than 85% of total European ETF turnover.

The European Commission’s Capital Markets Union (CMU) Mid-term Review (EC, 2017) acknowledged that the engagement of retail investors in capital markets remains very low, and highlighted the need to encourage ETF investments. Capital market participation of retail investors is suffering from a high degree of risk aversion and a heavy reliance on pay-as-you-go pension systems. As a result, currency and bank deposits (35%), insurance and pension fund reserves (32%) and equity (20%) make up the lion’s share of household financial assets, while just 10% is held in investment funds.[10] In contrast, 22% of the household financial assets in the US are held in investment funds (ICI, 2017). Particularly for ETFs, while retail accounts for around 45% of the US market, in Europe it is estimated at between 10-15% (Euroclear, 2017).

In order for retail investors to participate in capital markets, they need access to attractive investment propositions on competitive and transparent terms. While ETFs are successful in delivering the former, they fail – so far – to deliver the latter. MiFID I, implemented in 2007, did not recognise ETFs as an asset class, and therefore not all transactions had to be reported. This led to most of the market being traded bilaterally. It is difficult to tell exactly how much ETF trading takes place off-exchange, as figures are not publicly available, but estimates indicate that around 70% of all European ETF trading is taking place over the counter (OTC) and only 30% on-exchange, while the proportions are reversed in the US (AMF, 2017).

Given the small share of European ETF trading that takes place on-exchange, as well as the very low participation of retail investors in the market, it is natural to think that much of the on-exchange activity is due to the participation of retail investors. However, this does not appear to be entirely correct. Although the average trade size in EU exchanges (€48,395) is nearly double that on their US counterparts (€25,922), its distribution between electronic order book (EOB) and negotiated deals (ND), is very lop-sided.[11] On European exchanges, the average size of EOB transactions is just 12% (€30,420) of the average size of ND (€256,000). In stark contrast, the average size of EOB and ND transactions on US exchanges is almost identical (€27,642 and €23,698, respectively).[12]

Bilaterally negotiated trading involves no exchange costs and allows for much bigger trades (larger deals) – in direct interactions, investors can agree to trade any level of ETF shares, as opposed to being subject to minimum clip sizes in the case of exchange trading. However, while trading through an electronic order book incurs commission costs and brokerage fees, it benefits from the transparency and better execution implicit in being subject to regulation and therefore EOB transactions are typically used by retail investors. Larger trades – often part of institutional portfolio rebalancing or dealer inventory management (liquidity trades) – are typically negotiated bilaterally, so it appears that either institutional investors or large retail investors are the main component of the on-exchange market or that small European retail investors have not yet fully engaged in on-exchange ETF trading.

What is the way forward?

Regulation can and should certainly play an important role in the future of European ETF trading. However, the means for increased cost transparency are still inadequate. MiFID II, which came into effect on January 3, requires every ETF transaction to be reported and also envisages the establishment of a consolidated tape for financial instruments (equities, equity-like, and non-equity).[13] This should contribute to creating a more integrated European market, ensuring that consistent and accurate data is made available to market participants, and allowing investors to obtain a full picture of the trading volumes of a product listed across multiple exchanges. Despite this MiFID II provision, Europe (as opposed to the US) lacks a single reporting source (i.e. a single consolidated tape provider). While some efforts are underway within the industry to create a unified record of ETF trades in one place, this will take time. To this end, Commission is aiming to present a report on the functioning of the consolidated tape by the end of this year.

Distribution of ETFs to investors, particularly retail, appears to be one of the major obstacles. Banks could contribute by bringing more retail investors into the ETF market. In Europe, especially outside the UK, ETFs are sold to retail investors via banks and not via specialist brokers as is the case in the US.[14] As commission is the main driver, passive funds, which rarely pay commission, have been neglected by banks unwilling to market low-fee products. However, it is important to note the cultural difference between European and US investors. While the former have traditionally favoured a ’saving’ attitude, the latter have developed more of an active equity culture, for example in managing their pensions via defined contribution plans.

A mystery shopping exercise by the French Supervisory Authority (AMF) highlighted that products such as ETFs (among other low-cost investment funds) are not proposed/advertised to retail investors despite apparently corresponding to their investment needs.[15] In particular, the majority of online advertising of financial instruments is towards highly speculative trading and saving portfolios, and only 2% of the promotion is for exchange-traded products. However, with the implementation of MiFID II we should expect to see more ‘fee-based’ advice as in the US: as commission payments are banned, advisors are incentivized to keep fund costs low and move towards passive investment strategies. Moreover, ETF managers/advisors/promoters should continue their education and outreach efforts to promote and explain these products better to retail investors. Lack of education is the number one factor deterring investors from entering the ETF market. A survey study by Brown Brothers Harriman revealed that 49% of investors want to receive more educational information from ETF issuers (BBH, 2016).

Automated advice presents proven benefits, notably in easing access to ETFs and (relative) affordable advice. Technology can play vital role in bringing ETFs closer to retail investors, but also helping on the development of the product itself. As the management of data improves, so does the ability of index funds to capture different outcomes (e.g. thematic investing trends such as smart beta and ESG).[16] However, the boundaries are blurring between execution-only, portfolio management and advice business models and this creates uncertainty for retail investors. There is therefore a need for regulatory oversight of the algorithms guiding consumers through the advice process.

Settlement is a further issue with a major impact on the ETF market. While in the US all trades are settled in only one place (Depository Trust and Clearing Corporation, DTCC), in Europe there 29 central securities depositories (CSDs) in 26 countries.[17] As ETF trading occurs across a wide range of exchanges, a given ETF can listed on multiple exchanges and sometimes in different currencies at each exchange. Each exchange then has its own central counterparty (CCP) and CSD meaning each listing has to be settled in a separate location. Solutions aiming to centralise settlement and reduce transactions costs, such as Euroclear Bank’s International ETF Structure (covering Belgium, Finland, France, Netherland, Sweden and UK & Ireland) and ECB’s T2S, will simplify both issuance and post-trade processing in the European ETF market and enable a greater on-exchange liquidity provision.

The European ETF market has grown significantly and continuously since its inception in 2000, as investors are attracted by lower costs and simpler trading. However, in order for the market to reach its full potential, expand further and attain US levels, certain handicaps have to be removed. Over the coming years, regulation and technology can help the market: i) move from off-book, OTC trading venues to on-exchange venues, ii) develop a distribution channel to appropriately promote and adequately inform investors for such investment products, iii) enable a higher participation rate by retail investors, and iv) streamline settlement at a single location.

References

AMF (2017), “ETFs: Characteristics, overview and risk analysis – the case of the French market”, February 2017, Autorité des Marchés Financiers.

Antoniewicz, R. and J. Heinrichs (2014), “Understanding Exchange-Traded Funds: How ETFs Work”, Research Perspective 20, No. 5, September, Investment Company Institute.

Antoniewicz, R. and J. Heinrichs (2015), “The Role and Activities of Authorized Participants of Exchange-Traded Funds”, March, Investment Company Institute.

BBH (2016), “Emerging Trends in the ETF Market: 2016 European Investor Survey”, Brown Brothers Harriman.

Ben-David, I., F. Franzoni and R. Moussawi (2017), “Exchange Traded Funds (ETFs)”, Annual Review of Financial Economics, Vol. 9:169-189.

BlackRock (2017), “A Primer on ETF Primary Trading and the Role of Authorized Participants”, Viewpoint, March, BlackRock.

CBOI (2017), “Exchange Traded Funds”, Discussion Paper, Central Bank of Ireland.

EC (2017), “Mid-Term Review of the Capital Markets Union Action Plan”, Staff Working Paper SWD(2017) 224 final, European Commission.

Euroclear (2017), “A new dawn for Europe’s retail ETFs”, November 2017, Euroclear.

ICI (2017), “2017 Investment Company Fact Book: A Review of Trends and Activities in the Investment Company Industry”, Investment Company Institute.

Madhavan, A. (2016), Exchanged-Traded Funds and the New Dynamics of Investing, Oxford University Press.

[1] By the end of 2017, the US represented 71% of the global ETFs AuM, while the remaining 13% was distributed between Japan (5.8%), Asia Pacific (3.6%), Canada (2.5%) and Latin America/Middle East and Africa (1.1%). It should be noted, however, that the US market dates from 1993, seven years before the European one (2000).

[2] According to the Markets in Financial Instruments Directive (MiFID II, Directive 2014/65/EU) an ETF is “… a fund of which at least one unit or share class is traded throughout the day on at least one trading venue and with at least one market maker which takes action to ensure that the price of its units or shares on the trading venue does not vary significantly from its net asset value and, where applicable, from its indicative net asset value”.

[3] In an OEMF, individual investors interact with the fund directly and buy/sell (i.e. subscription/redemption) shares at the end of the day at the fund’s net asset value (NAV). If more investors subscribe to the fund, its assets and the number of shares outstanding increases. This process of creation and redemption is called primary process. On the other hand, in a CEF, investors buy/sell shares on the exchange intraday. Given that the size of the fund is fixed (i.e. closed-end) both in terms of asset and shares, secondary market liquidity determines the price at which shares are bought or sold.

[4] They can generate returns from: i) the difference between the NAV of the ETF and the aggregate price of the underlying basket of securities, ii) the bid-ask spread of ETF shares traded on the secondary market, or iii) commissions and fees paid by clients for creating and redeeming ETF shares.

[5] Directive 2004/39/EC.

[6] Directive 2014/65/EU.

[7] Directive 2009/65/EC.

[8] Consultation paper: ESMA’s guidelines on ETFs and other UCITS issues (ESMA/2012/44); Report and Consultation paper: Guidelines on ETFs and other UCITS issues (ESMA/2012/474); Guidelines for competent authorities and UCITS management companies: Guidelines on ETFs and other UCITS issues (ESMA/2014/937); 2018 Work Programme (ESMA20-95-619).

[9] Except cases where the stock exchange value of the shares of the UCITS ETF significantly varies from its net asset value, for example in cases of market disruption leading to the absence of a market maker. Therefore, the UCITS ETF is required to disclose the process for this direct redemption option in its prospectus, as well as the potential costs involved.

[10] Equity includes listed/unlisted shares and other equity. Debt securities account for 3% of financial assets. Data refer to 2017Q3. ECB Statistical Warehouse.

[11] Trades through an electronic order book (EOB) are placed by trading members and are usually exposed to all market users. They are automatically matched according to precise rules set up by the exchange, generally on a price/time priority basis. On the other hand, trades carried out through negotiated deals are confirmed through a system managed (directly or indirectly) by the exchange, where both seller and buyer agree on the transaction (price and quantity). This system checks automatically if the transaction is compliant with the exchange’s rules, and in most cases if there is consistency with the EOB price. Figures are author’s elaboration using data from FESE and WFE.

[12] Off-exchange venues, which serve institutional investors, are becoming important players in the market. For example, Tradeweb – one of the largest institutional ETF trading venues in Europe – reports that more than €165 billion in European-listed ETFs were traded through its electronic request for quote (RFQ) system in 2017, with an average trade size of €2.5 million.

[13] The consolidated tape is an electronic program which provides real-time data on volume and prices for ETFs.

[14] In the US, for example, brokers are required to route trades to the exchange that has the most competitive price for buying and selling an ETF at any given time. If more than one exchange shows the best price, the broker can choose.

[16] Smart beta ETFs offer a versatile, hybrid strategy (between passive and active management) with better risk-adjusted returns than traditional index products. Environmental, social, and governance ETFs invest in social responsible companies.

[17] ESMA: Relevant Authorities for Central Securities Depositories (CSDs) as at 15 December 2017.

Apostolos Thomadakis, PhD, is Researcher at the European Capital Markets Institute (ECMI).

ECMI Commentaries provide short comments on developments affecting capital markets in Europe. They are produced by specialists associated with the European Capital Markets Institute, which is managed and staffed by CEPS. Unless otherwise indicated, the views expressed are attributable only to the author and not to any institution with which he is associated, and do not necessarily represent the views of the ECMI.

www.eurocapitalmarkets.org, [email protected]

© Copyright 2018, Apostolos Thomadakis. All rights reserved.

-1300x731.jpg)

-20x15.jpg.webp)