Mario Draghi, the former head of the ECB and author of the now infamous (at least in Brussels) Draghi report, declared during a recent speech that the EU shouldn’t just rely on being an economic regulator if it doesn’t want to be sidelined by the US and China, the world’s foremost superpowers.

Indeed, the EU’s summer of summits and new trade deals with China and the US yielded far less than expected. But the EU’s regulations aren’t to blame.

Regulations follow markets but regulations also shape markets, and they impact who ultimately dominates said markets. And this is why the EU shouldn’t throw away its regulatory role, the so-called Brussels Effect – even today, it’s still one of the most powerful and influential tools in its arsenal.

Yes, the EU should be more of an industrial power – and maintaining and preserving its regulatory heft, rather than jettisoning it, can actually help it to achieve that goal. To have and to retain real global leverage, the EU needs to reassert its power in what it’s already good at.

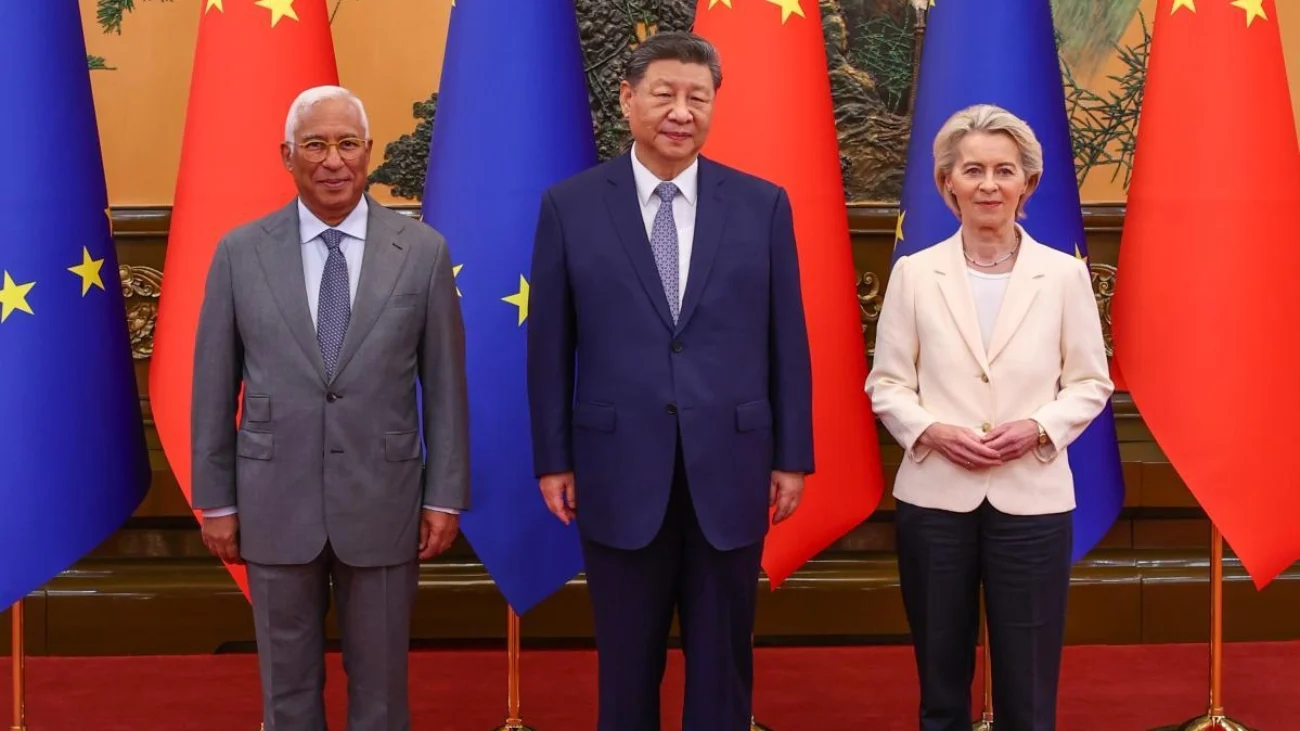

The EU-China Summit – proof that regulatory power is still legit

At the EU-China Summit on 24 July, little progress was made on major disputes, including European concerns over Chinese overcapacity and unfair competition in emerging technologies, which Beijing refused to recognise as market distortion.

Ultimately, no joint statement was issued, reflecting entrenched divisions over trade imbalances, industrial overcapacity and China’s stance on Russia’s war in Ukraine. The only exception was a short, vague climate communiqué, carefully worded to avoid binding targets or new pledges. Whilst this underscored the EU’s reluctance to endorse rhetoric without concrete Chinese commitments, it nevertheless signalled that both sides still see value in presenting at least a minimal shared interest in global governance.

Still, Commission President von der Leyen struck a deliberately constructive tone in the press conference, stressing that China’s industrial overcapacity stems largely from its domestic economic structure and investment-driven growth model, rather than an intentional strategy to undermine European industry.

However, China’s industrial overcapacity and the consequent flooding of European markets are only the tip of the iceberg. The EU cannot outpace China quickly enough through protective tariffs or domestic re-industrialisation alone. Instead, it must focus on containing and slowing China’s advance in emerging markets by leveraging its regulatory power, since whoever sets the rules and standards for new technologies usually goes on to dominate those markets.

That’s why an essential, yet silent, power struggle is being waged in the field of standard setting for emerging technologies, such as new green energy sources and critical raw materials mining and processing. Both the EU and China are trying to shape industrial production standards in a way that would protect and promote their own manufacturers.

And this competition is why Draghi’s call for ditching the EU’s economic regulator role is premature. The EU’s tussle over standards with China, a key reason why the Summit can’t be celebrated as a shining success, is a prime example as to why EU leaders should be working to reinforce the ‘Brussels effect.’

Regulatory convergence – the EU’s still in the game

This summer began with the (mostly) inconsequential EU-China Summit, stumbled through a lopsided EU-US trade deal, and culminated in the Alaska Summit, which outrageously shut Europe out. To add insult to injury, China, meanwhile, managed to successfully postpone US tariffs and orchestrate a potential easing of the chip war.

As these tumultuous events demonstrated, Europe is nowhere near reindustrialising fast enough to be a sizable competitor in critical sectors and the US-China trade war puts the EU between a rock and a hard place.

The challenge is derisking from both superpowers in the next Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF) period, when there’s no blanket formula for the EU due to sectoral and regional differences. However, even with a lack of industrial capacity, a long-standing commitment to regulatory frameworks is a huge advantage. The EU – unlike China – has deep experience in working with global governance institutions and wielding tools such as coalition building and norms diffusion.

The Brussels effect is particularly evident with China, which has aligned with the EU’s GDPR and Deforestation Regulation. There’s also a track record of outsourcing ESG tracking to European firms in African countries rich in critical raw materials (CRMs), as European firms are globally recognised for their CRM-related services. For geostrategic tools such as the Global Gateway and new instruments like clean trade and investment partnerships (CTIPs), providing ESG compliance assessment for Chinese investments in partner countries is one way to mobilise the European private sector.

However, such complementarities shouldn’t be taken as a given because not all EU regulations are welcome anymore in the ‘battle of offers’ era. CBAM and the CSDDD have been criticised for their non-inclusive and burdensome nature, even by the EU’s like-minded partners. The simplification process in this institutional cycle is a welcome response to these criticisms.

More pressingly, China is expanding its role in standard-setting and compliance assessment. Thanks to initiatives such as ‘China Standards 2035’, China has dominated the standard-setting processes in international organisations in many emerging fields, including telecoms and the Internet of Things (IoT).

Regulate to compete

The EU-China Summit and EU-US tariff deal tell us that the EU intends to keep hedging between the two superpowers – but crisis avoidance on its own isn’t a sustainable strategy. The EU must decide what role it will pursue in the China-US clash over critical technology markets.

That’s because achieving strategic autonomy through complete industrial self-reliance simply isn’t possible. Nevertheless, the EU is internationally recognised for its capacity to shape rules and standards in emerging technologies, with its regulations (still) often emulated by international organisations, partner countries and even competitors like China.

To remain competitive and independent from both superpowers, the EU must continue to play to its strengths and not hesitate to throw down its most powerful cards – this means leveraging its substantial regulatory expertise and institutional capacity to influence standards for newly emerging critical technologies.

Using this to its advantage and baking it into how it approaches its relationship with China (and the US) would help to secure supply chains in sectors where it’s simply not competitive enough, quick enough or cost-effective enough to rebuild its industrial base.

The ‘Brussels Effect’ is still a force to be reckoned with – it would be foolish for the EU to disregard it.